To our right, sightseers crane necks out of car windows for a look at the gravity-defying Dall sheep. To our left, they wield binoculars, scanning for humpbacks and orcas. In between lie a series of long, lurid skid marks. It’s not quite wilderness, here along the Cook Inlet, but methinks it could get wild.

And we haven’t even left the municipal boundaries of Anchorage, Alaska. In less than an hour we’ll have traversed this city of a quarter-million, traveled the length of the state’s only divided highway, watched a Winnebago go up in flames and bid farewell to our last traffic signal in a thousand miles.

Phil Freeman, owner and chief guide of Alaska Rider Tours, promised that we’ll have seen “more of Alaska than most Alaskans” on the six-day Prince William Sound Ferry Tour. Our route lies almost wholly in the shadows of North America’s most prodigious mountains, but you don’t go to Alaska for mountain riding per se. Hatcher Pass will be the most curvaceous ascent for our 650cc dual-sports. After maybe 10 miles of delectably banked asphalt(with loose marbles) it crests at a mere 2,300 feet and winds unpaved down the other side.

Though the pass opened only three short weeks ago, not a trace of snow still remains. The days of summer are few but long at this latitude. Gathered ‘round a campsite at 11 p.m. with good company you savor how lazily they slip into night.

You must meet our group. There’s Bob McAnally, a DJ from Pinson, Alabama. For a beer he’ll regale you with a car commercial, Alabama style. He says his friend Rick Jones, from Springfield, Missouri, is “the most enthusiastic guy I’ve ever met,” and it would be hard to argue. The retired International Harvester manager and his wife had just returned from a motorhome trip—to Alaska—when Bob proposed the bike tour. Now he’s over in the creek, wrestling with a king salmon hooked on tackle provided by our guides.

Steve Cross is a public utilities exec from Wellington, New Zealand. He reads a lot and scribbles assiduously in a journal, but he’s quietly suffusing our group with Kiwi witticisms. “Stackin’ zeds” and “a good old rogering” will become part of our tour vernacular. And we’ll not forget the tale of Baa-aa-aa-aa-ry, the dual-sporting veterinarian who freed a poor lamb whose head was stuck in a fence…but not before the next wave of riders crested the hill and spotted him grappling with it in the waisthigh grass.

At the conclusion of each day’s ride, Freeman loses the helmet and dons his chef’s hat. Teriyaki steak and poached halibut are just a couple of his specialties. He’s ably assisted by Akiko Morikawa, a 33-year-old free spirit who five years ago fell in love with the Alaskan outback on Freeman’s very first Alaska Rider Tour. Akiko, who rides a Yamaha XT225 back home, is also group photographer and copilot to Justin Grebe, driver of the sag wagon.

In 24 hours 26-year-old Justin manages to a) lose a wallet, b) hitchhike 60 miles with a blown trailer tire c) drop in on a book signing party d) find a missing article of clothing in a junkyard and e) deliver the camp supplies—on time.

Chad Sundry, age 29, rides sweep for the group. A Utah native, Chad’s a certified motorcycle mechanic who migrated to Alaska for the hunting, fishing and skiing. Each night, while he doggedly screws our bikes back together, we gorge on the smoked salmon he’s rumored to have canned with his homemade two-stroke blender.

Morning two. We vote unanimously to continue up the Petersville road, an old mining route, now serving drivers of high-clearance vehicles the most unspoiled views of Mount McKinley. Thirty-four miles long, it grows rockier, muddier and steeper. For Bob, whose only previous off-road experience was some backyard minibike riding, this is motorcycling Outward Bound, but he works out his rhythm and negotiates the entire length without a spill. Collectively, we’ll bag a couple of thousand miles of dirt road without a handlebar ever touching the ground.

Riding toward Mount McKinley (20,320 feet) is like sneaking up on the sun. We crane our necks to see its summit, but it’s still a hundred miles off! Alaskans claim that it’s the world’s greatest mountain, several thousand feet taller, from base to summit, than Everest. And since its peak can be reached without oxygen or expedition funding, it’s a “peoples mountain.”

Mind you, Alaskan people might be made of different stuff. At Cantwell, said to have the nation’s largest concentration of Vietnam vets and FBI most-wanteds, we bump into two of Phil’s hometown pals. They’ve just completed a 150-mile adventure race (that would be a foot race) through the Denali Wilderness, and their feet look like sausages about to burst on the grill. It’s a record 90 degrees down here on the Parks Highway, but they’ve braved, among other things, an overnight blizzard dumping 18 inches of snow.

On the Denali Highway, we turn our backs to McKinley and spread out, escaping each other’s dust clouds and reaping the solitude of the immense plateau which precedes the Alaska Range to the north. The trees here are sparse and low, yet somewhere 30,000 caribou are hiding even lower to escape the sun’s penetrating rays.

Our group’s arrival probably triples the population of Gracious House, Alaska, but with an airstrip, campground, guesthouse and bar, it’s the “capital” of the Denali Highway. It’s also the final resting ground for just about anything with a motor…a ‘57 Caddy, a ‘30s era pickup of indistinct lineage, an airboat and a pair of early Japanese trailbikes. The museum tour could go on and on, but a loud tortured wail in the nearby brush sends us off in pursuit of a very large sounding beast, armed only with half-full beer cans. Phil, whose wit can be as dry as this August heat wave, claims to have enough material for a northwoods tell-all book, “Moose Maulings”—including the tale of a motorist who attempted to confirm a road kill with a rather ill-advised probe.

“If you survive a bear attack the guys at the bar will at least buy you a beer,” says Freeman, building his case for the alleged cover-up “…but who will admit to being molested by a herbivore?!”

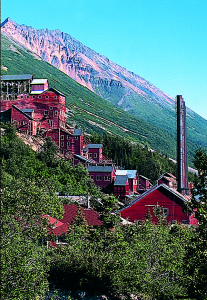

Wrangell-St. Elias is the nation’s largest national park, home to nine of North America’s 16 tallest peaks. Along the

McCarthy Road their images are painted in mirror smooth lakes speckled by trumpeter swans and framed by cotton grass and fireweed. Phil, who’d set us up for a dusty 60-mile blast, makes a difficult admission as we pause at a 400- foot-high railroad bridge.

“This is the first time I’ve seen those mountains. In five years of tours, it’s never been this clear!” We arrive at McCarthy just hours after the ice breaks on the Kennicott River, sending the town (25 permanent residents) into a frenzy of impromptu partying.

It’s been a long day, and after touring the copper mine ruins the group heads back to the campground at Kenny Lake, but I elect to hike down to the Kennicott Glacier. Until this year, Freeman, only 32 but a world traveler, fluent in Spanish, Portuguese and Japanese, catered solely to Japanese motorcyclists. He confesses he’s just learning about the American rider’s greater need for independence, but I’m grateful for the loosened reins as I scramble down the winding trail and onto the swelling sea of blue ice.

The rest of the group samples this otherworldly trekking the following morning at the Worthington Glacier on Thompson Pass. Halfway up the pass though, we sight a monster, and it’s steamrollering angrily toward us. Faster than we can don our rainsuits the temperature plunges and visibility slips to nada. Just like that the great northern summer has become a fond, fleeting memory.

The port of Valdez, terminus of the Alaska Pipeline, is enjoying a pleasant fall afternoon. While Rick and Steve fish for our last camp dinner, Bob tours the local museum and I explore another mining road, this one leading up a canyon lush with wildflowers and towering waterfalls. In solitude, I pick salmon berries as my contribution to the special meal. I do so surrounded by a symphony of water sounds—from a faint tinkle to an oceanic roar. A few hours later, in a soft drizzle, I fall asleep at the campfire and have to be nudged to my tent.

It’s dark when we receive the trip’s only wake-up call. In six spins of the globe we’ve watched nighttime boldly snatch hours away from day. On the four-hour crossing of Prince William Sound, we spot sea lions, kittiwakes

and an eagle or two. In the fog we make out traces of icebergs, but it’s far too soupy for the anticipated whale watching. The dreamy gray crossing seems a fitting come down from the Disneyesque days on the road.

My tripmeter reads 1,060, group exuberance having pushed us nearly 300 miles beyond the published itinerary. Perhaps half the total came on dirt and gravel roads for which the Suzuki, Kawasaki and BMW 650s proved well suited. Riders with some off-road experience (which Freeman strongly recommends) will not find the routes technically demanding. Attirewise, layers are the way to go. The tour season runs from May 15 to September 15, when average temperatures are pleasantly temperate—but wintry weather is never too far off.

At about $3,000, this ride ranks just on the high side of one-week tours. If you equate value with lots of twisty pavement or the number of stars embossed on your hotel portal, then you’ll probably be disappointed. If you’re put off by dust, you’ll not be happy (although the mosquito and black fly menace proved largely apocryphal). There’ll be no chocolates on your pillow unless you pack both, but sturdy tents and cots with extra sleeping bags (riders are advised to pack a three-season bag and a towel) ensure that you’ll sleep well at the end of a long ride.

Setting up camp is a lot more difficult than flashing a credit card at the end of a 200-mile day, and this was the best staffed, hardest-working tour operation I’ve ever traveled with. They cheerfully handle all the camp chores, although I suspect most riders who sign on for a such a tour will want to pitch in. I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend the tour to inexperienced campers. Camping tours start and end with B&Bs, however all three guests from the lower 48 skipped out early, owing to the high percentage of red-eye flights leaving Anchorage.

Criticisms? Even off-road-equipped motorcycles can’t venture where float planes and canoes can, but I would have preferred to camp beyond the reach of motorhomes. I think that an evening backpack followed by a midweek B&B would spice up an already flavorful itinerary. Freeman also offers a non-camping version for $500 more, plus three other Alaskan routes and specialty tours on demand.

Unlike most organized tours, you almost can’t spend money on an Alaska Rider Tour. The package includes every meal, snack and libation, plus all of your gasoline and a pricey ferry crossing—costs that would mount quickly in a region where nearly everything must be flown in. The only thing Freeman doesn’t cover, curiously, is your shower— three or four bucks should you ever feel the need.

I would, however, recommend that any visitor stash a Ben Franklin for a 90-minute bush flight. And try to schedule it early, because you never know when the mountains will disappear.

Alaska Rider Tours

P.O. Box 1392, Girdwood, Alaska 99587

(800) 756-1990 or (907) 783-1990

www.alaskarider.com